Transitional Governance Today: A Risk and Opportunity for International Law

Dr Emmanuel De Groof is a scholar in the fields of international law, diplomacy, and development cooperation. His forthcoming book, ‘State Renaissance for Peace’, is a treatise on Transitional Governance under International Law. In this post he introduces his new PA-X report, The Features of Transitional Governance Today.

I. A formidable expectation: peace and stability

Constitution-making, and external assistance to it, are phenomena known since quite some time. In 1758, international lawyer and diplomat Emmer de Vattel accepted that outside states may sometimes act as mediators of constitutional affairs.

Today, as shown in this Spotlight report (‘the report’) the societal and diplomatic function of (external assistance to) constitution-making against the background of regime transitions has considerably evolved. Since 1989, regime transitions have become increasingly disassociated from decolonization, secession or dissolution processes. They have become processes to bring peace and stability – no less – through a wholesale constitutional and institutional transformation.

More recently, two additional trends can be spotted through the political and diplomatic saga, and sometimes the activity of the UN Security Council and regional organisations, surrounding the unraveling of the Arab Spring, the war in Ukraine, political and social crises in various countries around the globe for example in Algeria, Nepal, (South) Sudan, and Venezuela (with many more examples in the report):

- External actors – both states and various organizations – actively engage with (intended) transitions abroad in today’s era of ‘constitutional geopolitics’.

- Constitutionmaking unfolds against the background of a larger transition, i.e. transitional governance by interim governments or transitional authorities (TA).

Transitional governance (TG) then broadly concerns the interim rule during the entire period, a matter of months and often years, of a state’s constitution and apparatus being overhauled, especially in the context of an armed conflict, or a threat to international peace and security.

II. Contemporary characteristics of transitional governance

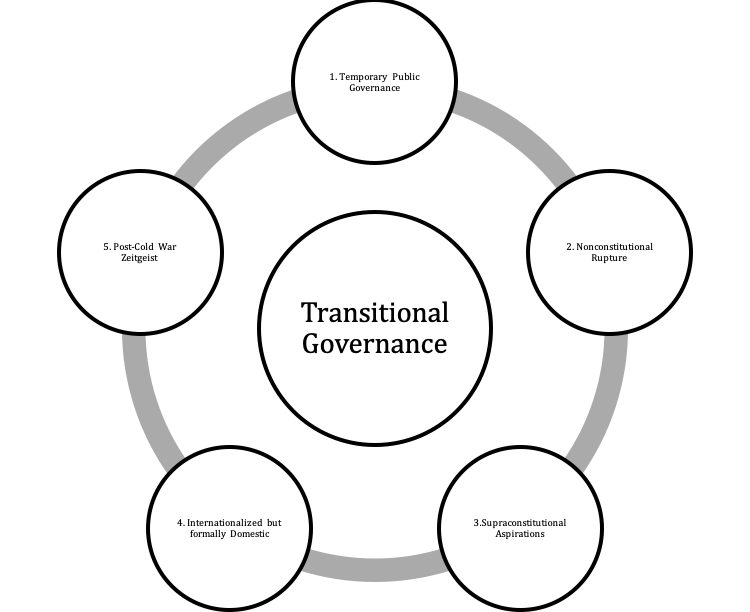

By unveiling the current factual features of TG, the report lays the groundwork for an analysis of how international law – as it currently stands and as it may develop – applies to TG. The report suggests that five features of TG can increasingly be observed:

- Legal internationalisation. Increasingly, transition instruments provide that public authority during the transitional period must be guided by international legal norms.

- Time-limited. The transitional period is limited in time, and TG, even if programmed to last for a long period, is specified not to be prolonged artificially.

- Functionally limited. TA must concentrate on administering the country on a provisional basis, including by restoring security, and by preparing for the future without foreshadowing their own transition to power.

- Inclusive. Over the last decades, ‘inclusivity’ and ‘domestic ownership’ have been systematically promoted in relation to TG. This is palpable especially in relation to women’s groups (as the report Women and the Renegotiation of Transitional Governance Arrangements shows).

- Transitional Justice. State practice amply confirms the conviction that transitional justice is part and parcel of TG, as another report also suggests. In the vast majority of cases, TA are required to address the past in one way or another, and to ensure that this exercise is ‘owned’ by the population of the state in transition.

III. The role and risks of socialisation

Why have these five features become common currency? The five-fold dominant discourse and practice is arguably the result of acculturation within a small epistemic community. The community of practitioners engaged in post-war countries and constitution-making is constantly growing. Yet, the epistemic community dealing with these issues is rather modest in size. This creates a habitat favourable to emulation. Also in the future, the five features just mentioned are likely to be further socialised by practitioners including constitutional experts, diplomats and mediators.

Yet, the contemporary approach to TG has not been fruitful, quite on the contrary, as Bell has argued elsewhere:

‘A quarter of a century of investment in transitions has seen a specific new international and regional architecture built to address transitions, new international norms promulgated, and expensive development and governance interventions embarked on. It is now apparent that these efforts have failed to lead to democracy and peace taking hold worldwide, for several different reasons’.

Should we therefore reassess the practices and discourses undergirding TG? Whatever the case may be, let us finish here with a word of caution. The conviction that widely accepted practices would be deprived of any legal impact on the sole ground that they might not be – morally or politically – commendable, is a bit of a short-cut.

One cannot, for example, simply ignore recurrent commitments to ‘inclusion’ or ‘ownership’, which sometimes seem to have adverse effects or to unduly prolong the transition, merely because such practice ought to be subjected to a deeper, and certainly welcome, policy critique. In sum, we should be wary of the jurisgenerative connection between socialised deontology, constitutional or supraconstitutional texts, and international law.

IV. The need for further debate

While international law without doubt constitutes a usefool tool for debating the geopolitical and state-to-state implications of TG today, the law itself is not hermetically shielded from repeated practices and beliefs, which may positively or negatively affect its tenets and development. Here lies both an opportunity and a risk. And this is precisely why reconciling action with reflection is so elementary in diplomatic practice and deontology.

Observing the contemporary features of TG form the necessary basis for further critical reflection. As a simple perusal of facts and practices, the report lays the groundwork for critical analysis on TG in two books, which you are warmly invited to look into:

- State Renaissance for Peace – Transitional Governance under International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2020)

- International Law and Transitional Governance – Critical Perspectives (Routledge, 2020)

Ultimately, both books intend to frame and hopefully elevate discussions on regime transitions. Their aim is indeed to provide legal parameters allowing for an informed legal debate on a topic which is simply too important to be left unaddressed.

As a state’s own renaissance affects the political fate and social well-being of its citizens. Millions of people are concerned worldwide. The topic of TG is thus no fait divers, and deserves to be critically approached by a growing number of scholars and practitioners.

Read the report in full: The Features of Transitional Governance Today

Disclaimer: This blog represent the author’s views and not necessarily those of the institution(s) he is called on to represent.

Image: Jacob Jordaens, Ferry to Antwerp. Courtesy of SMK, National Gallery of Denmark; Photo credit: Jakob Skou-Hansen via Wikimedia